The American phone company AT&T had created the Western Electric (Westrex) research laboratory years before to investigate technology for its clients. Engineers like Dr John Frayne and John Jacobs invented new ways of recording stereo sound that were ultimately used in nearly every Fox, MGM, Paramount, Columbia and Universal feature film.

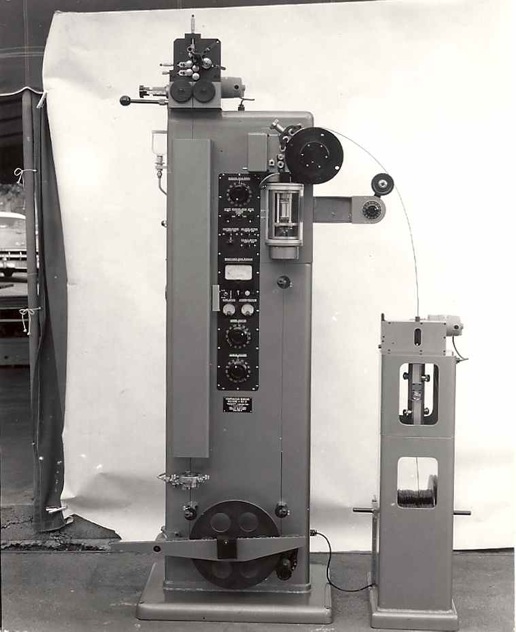

It wasn’t surprising then that the same clients asked Westrex to create a quiet film editing device.

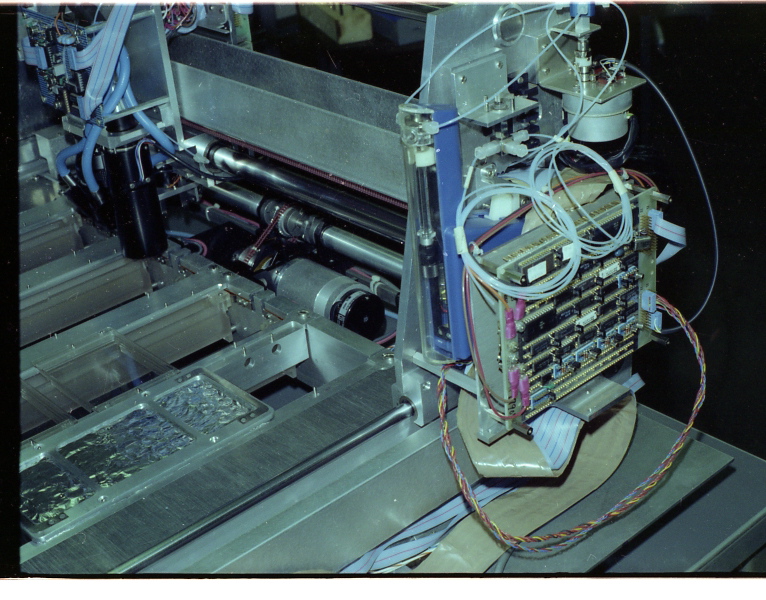

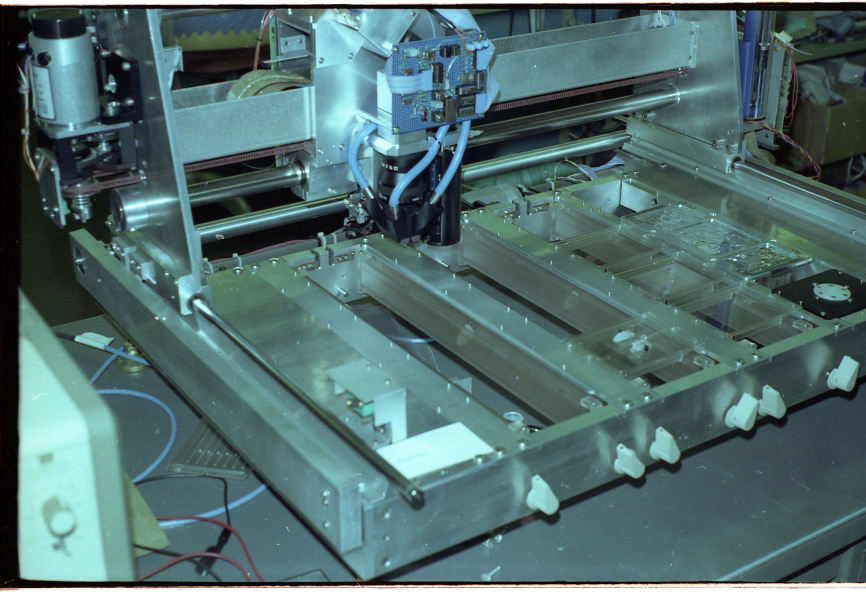

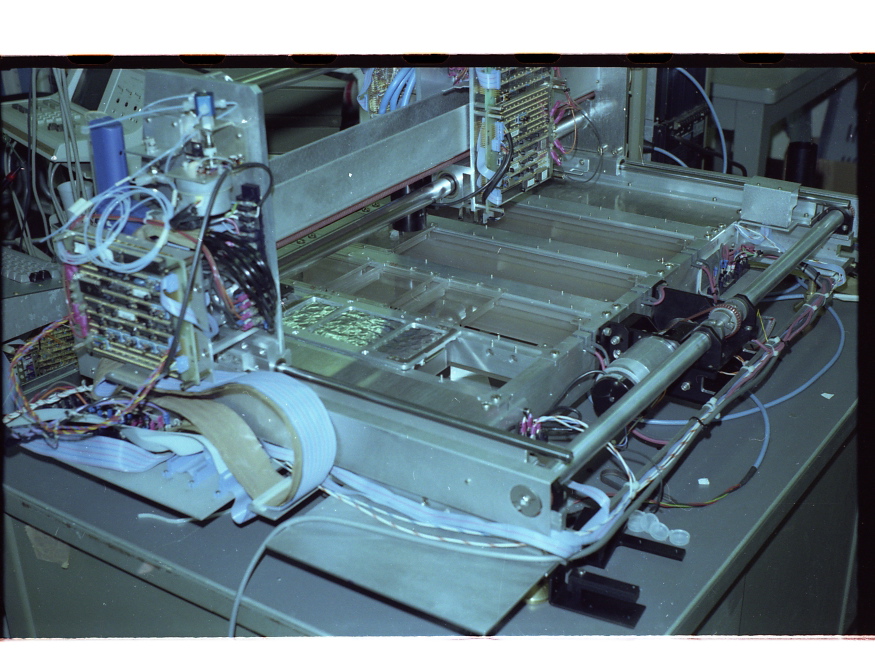

Through 1952 a highly experienced team at Westrex’s Hollywood division on Romaine Street worked to find a better way to edit sound films. Fred Hauser, Lewis Browder, George Crane and Herb Manley researched and built various elements of a new device and spent time with Hollywood editors asking them for feedback on proposed 35 mm editing table.

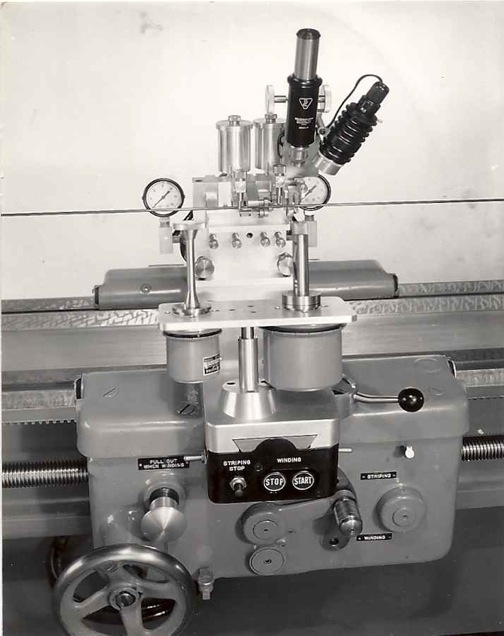

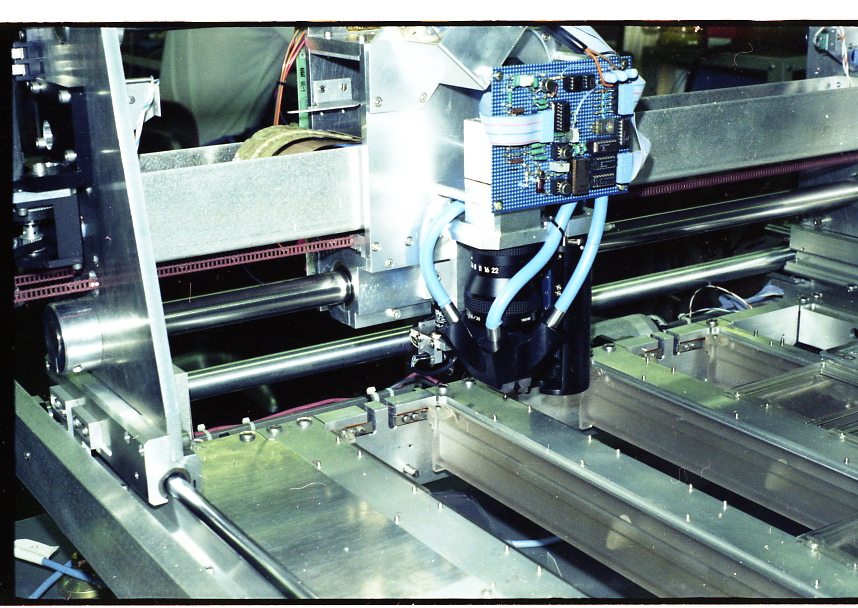

Browder was an expert in projection and applied the prism technology employed in high-speed cameras and projectors to the planned device. Hauser, a mechanical engineer, focused on the film plate and gate to guide sound picture rushes through the apparatus.

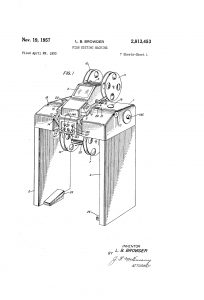

A day after Browder filed to patent a ‘film editing machine’ on April 22 1953, Crane publicly announced the the Film Editer (with two e’s). He explained to a SMPTE meeting what they had achieved.

A film editing machine which employs continuous projection resulting in quiet operation. It accommodates standard-picture and photographic or magnetic sound film as well as composite sound-picture film. Differential synchronizing of sound and picture while running, automatic fast stop and simplified threading features in the film gates with finger-tip release materially increase operating efficiency.

Crane believed that they had ‘solved’ the Moviola’s noise problems by using:

“…continuous optical projection and the substitution of timing belt drives for gear driven mechanisms…”

In short the Editer was quiet.

The engineers used teethed belts instead of the noise making metal gear mechanisms on the Moviola. The Westrex machine was also much simpler to thread , yet not easy to slip sync.

“…placing the film in the film trap automatically locks the film to the drive sprocket so that the position of the film cannot be lost inadvertently.”

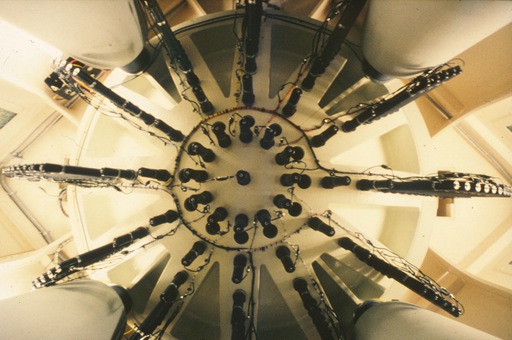

Browder had enhanced the previous work of engineers Bill Harrison and Franz Ehrenhaft in prism projection. The Editer’s rotating 12-sided prism enabled smooth viewing on the editor’s screen as well as enabling it to project images to an adjacent wall for a director’s screening.

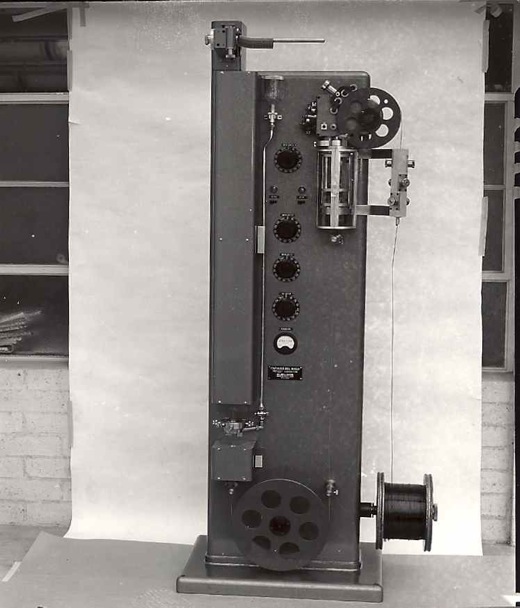

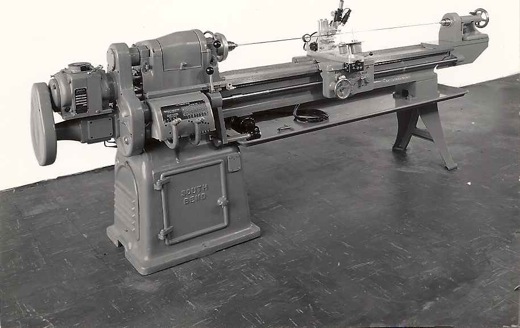

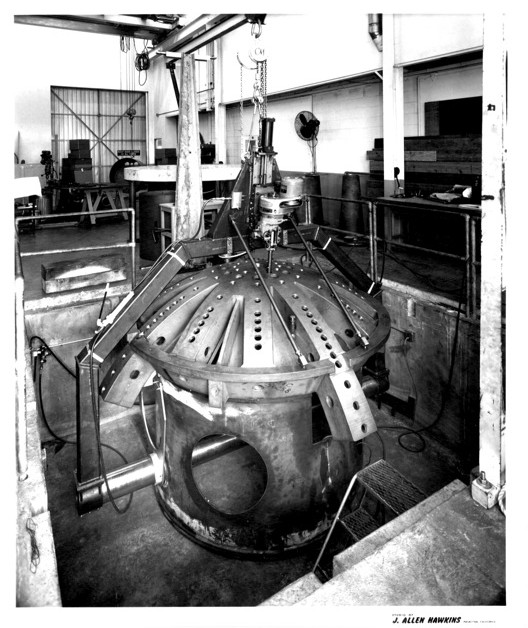

Westrex commissioned a South Pasadena based manufacturing specialist, Boller and Chivens to build the units. Boller and Chivens had previously made precision equipment like wind tunnel strain gauges and film camera viewfinders.

Boller and Chivens built a special motor for handling the film and sound rushes at a variety of speeds and then constructed the iconic aluminum console that could be operated standing up, or sitting down.

A young Anthony Tony Buckley A.M. used a Westrex on location to edit Michael Powell’s adaptation of Norman Lindsay’s novel, Age of Consent. Buckley recalled in his autobiography, Behind a Velvet Light Trap.

“Despite having the windows and doors open, the film began sticking to itself. Worse, the mirrors on the Westrex Editer began to deteriorate, but the final straw came when I and the film I was cutting, were pulled into the machine. The moisture adhering to the celluloid was unbelievable.

An air-conditioner was requested and much to our surprise an air-conditioner arrived. (We) were soon working in the comparative lap of luxury, much to the envy of our fellow crew members.”

Westrex sold more than 50 units and won a technical merit Academy Award®.

“for the design and construction of a new film editing machine”

The company was asked to make an Editer to accommodate the editing of the Todd-AO 70 mm based musical South Pacific. The machine was modified to accommodate two 35 mm magnetic films, each containing six stereophonic sound tracks.

Thanks to John Buck for providing the above text from his book Timeline Digital

Westrex Editer – The patent papers

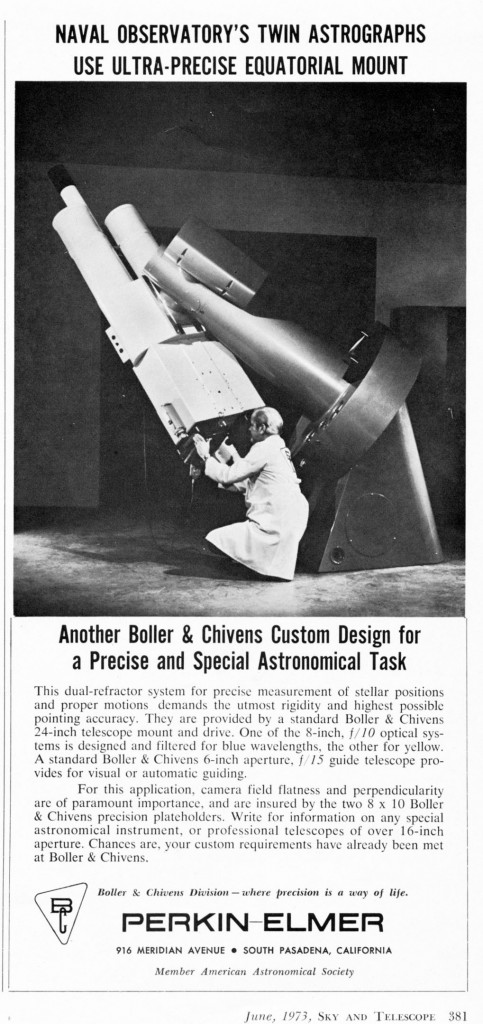

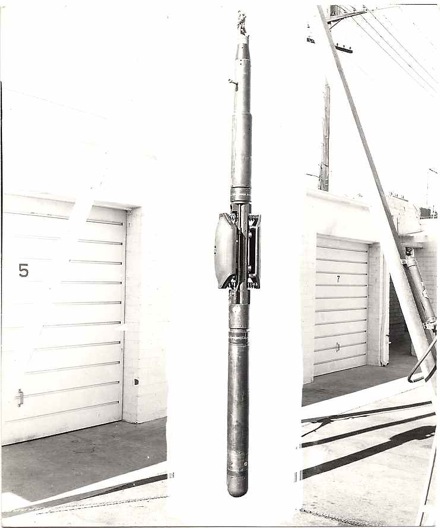

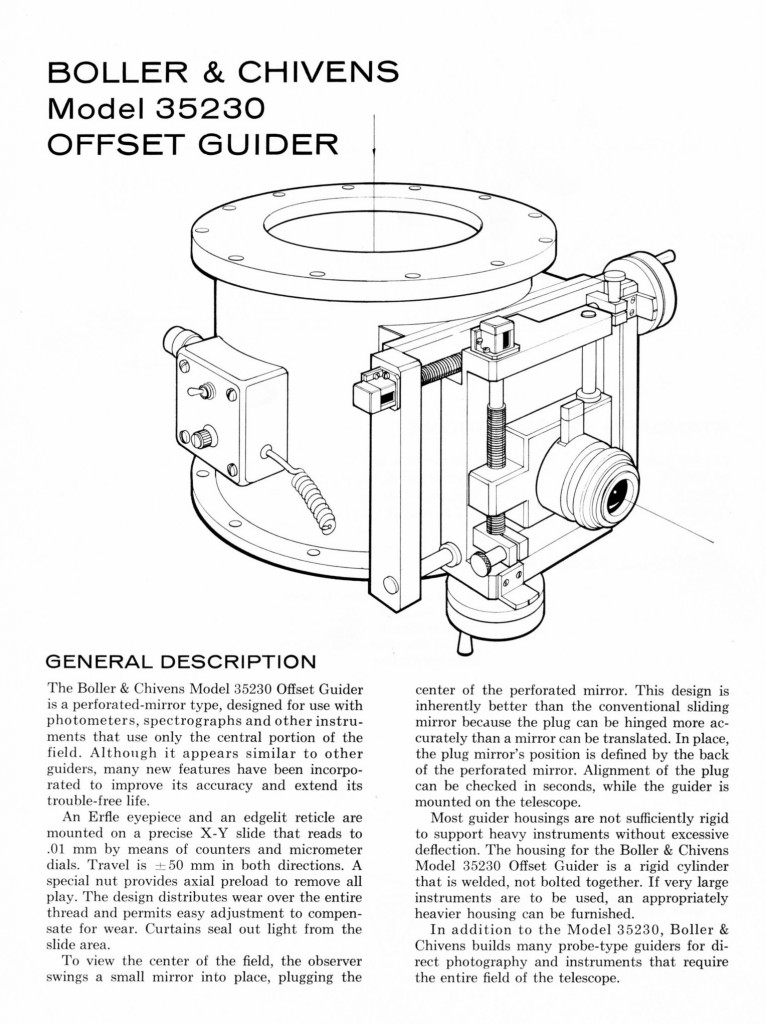

A 16cm by 16cm camera with two guiding eyepieces and manual shutter designed and manufactured by Boller and Chivens.

A 16cm by 16cm camera with two guiding eyepieces and manual shutter designed and manufactured by Boller and Chivens.